On Memorial Day weekend in May 2016, as part of Crosslines: A Culture Lab at the Smithsonian Arts & Industries Building—organized by the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center—I presented my first public installation drawn from my archival research on Langston Hughes’ stay in Turkestan (the pre-1921, pre-Stalin term for Central Asia, a vernacular that lingers when Hughes visits).

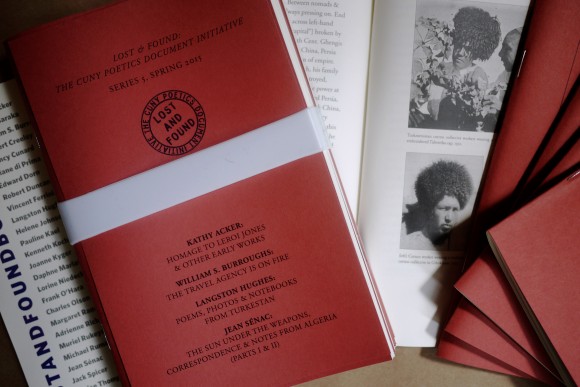

The installation was a modest but deliberate attempt to recreate the sensation of entering an archive: the intimacy, the uncertainty, the thrill of discovery. Beginning in 2014, my research at Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library and at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture had yielded poems, diary entries, and notes by Hughes that had never been published. I wanted to share not only the findings themselves but also the experience of archival research shaped by chance encounters, intuitive leaps, and moments that resist linear explanation. I dreamt of the Uzbek poets Hughes met and later encountered, and of untranslated poems in older Uzbek, the Uzbek language I grew up speaking, which I later translated for Lost & Found. Saed, Zohra. “Langston Hughes in Turkestan.” [Lost & Found CUNY Poetics Initiative], 2015. I am still translating and editing the final manuscript (here in 2026, ten years from this exhibit).

While the academic community has been deeply supportive of this work, the resonance of sharing it with a nonacademic audience was unexpectedly powerful. Over the course of the weekend, I spoke with families, travelers preparing to visit Central Asia, humanitarian workers, artists, spiritual healers, old friends, new acquaintances, and accidental tourists who wandered into the exhibition space.

I shared this immersive archival installation alongside my colleague Kai Krienke, who presented his work on Jean Sénac, and with Lost & Found editor Kate Tarlow Morgan.

The installation itself was spare: on a bare wall, a strip of muslin served as the projection surface. From one projector, I cast photographs taken by Hughes in Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan; from another, his handwritten notes and poems. A technician initially worried the setup was too minimal to register as an exhibition. In the end, the simplicity—and the fabric’s slight movement—lent the images a haunting, almost spectral quality.

It remains one of the most emotionally resonant experiences of my scholarly life: sharing archival work not as interpretation alone, but as an encounter. The remainder of that experience is best conveyed through the photographs below.

Leave a reply to Langston Hughes / Aziz Longston Xughes Research – Zohra Saed Cancel reply