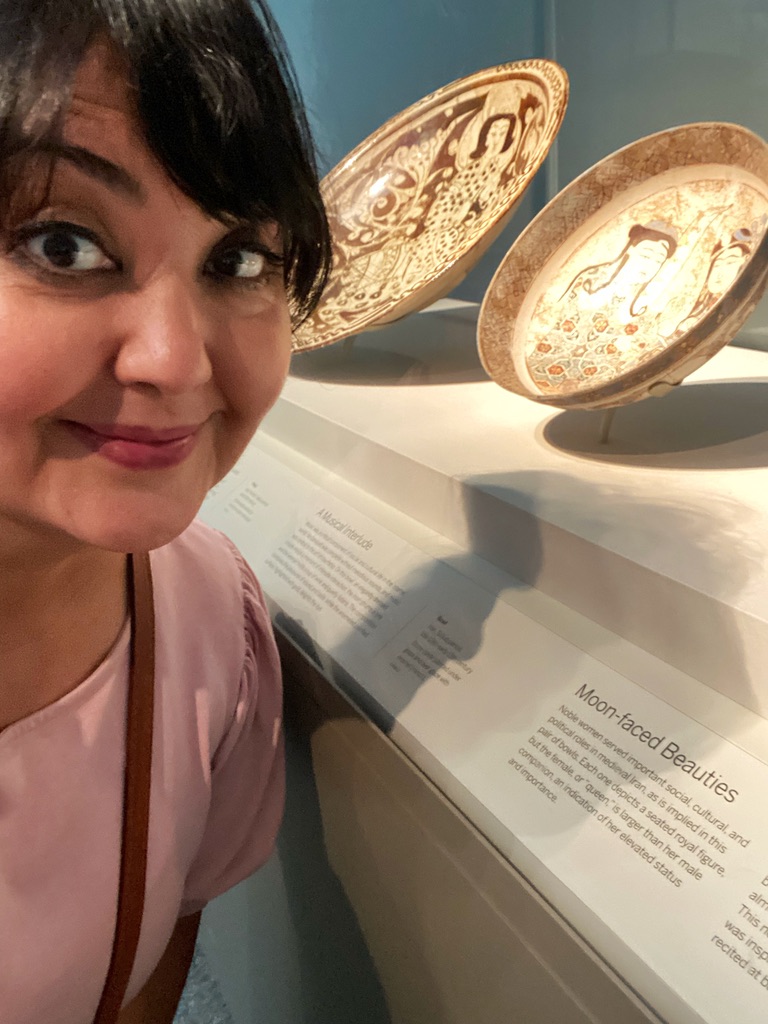

I learned that the word for beautiful in Uzbek, Chiroyli, or as we say it in the older Turki, Chiroyliq, means “face like the moon.” This is why in Uzbek/English dictionaries, you don’t find chiroyliq under pretty or beautiful– it is more than these words. It means “Beaming”. A face that beams.

Chera from Farsi means “face.” The moon is in every part of our language for beauty and glow. And in names, of course, oy or ay or ai prefixes or suffixes make up a great portion of Central Asian names. Even growing up in Brooklyn, I knew five sisters, each named Moon: Aygul, Aynur, Aysal, Aytan, and Qamar. In order of birth, Moon Flower, Moon Shine, Moon Beam, Moon Body, and the fifth sister are named after the moon in Arabic.

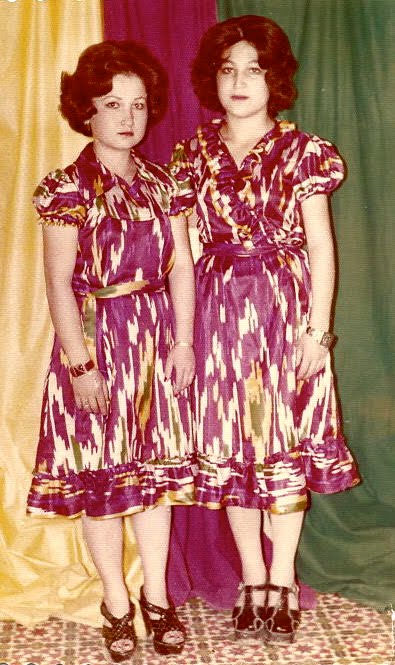

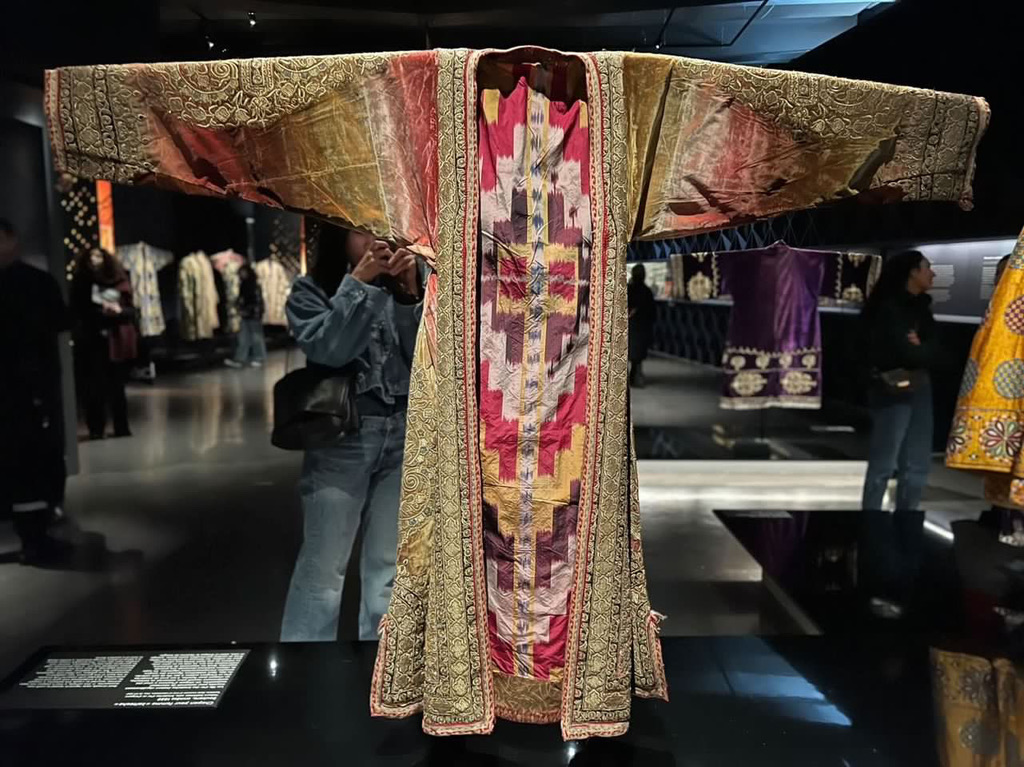

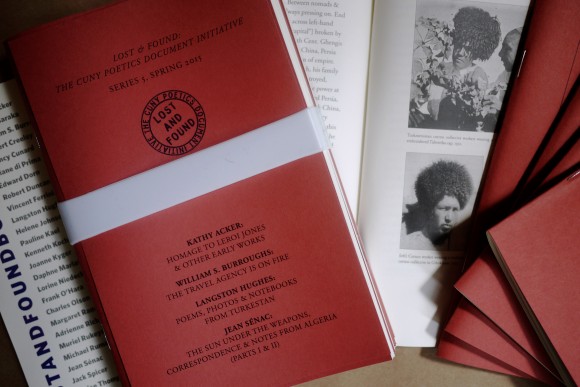

My maternal aunts, Jamila and Qamar, were born and raised in Kabul as the grandchildren of refugees from Turkestan. They grew up in the old part of Kabul and are pictured above in a Kabul photography studio. My Aunt Jamila, on the left, owned a small tailor shop that was quite popular in the 1970s and 1980s. In this photo, she is wearing a matching dress made from Uzbek atlas silk fabric, reflecting her contemporary take on traditional Uzbek designs.

Today, I see similar innovative styles showcased by Central Asian fashion influencers on Instagram, which reminds me of this photo of my Aunt Jamila in Kabul, where she was revamping her grandmother’s old dresses. During the Soviet era, there was an influx of traditional Uzbek fabrics entering the Kabul markets, which Jamila took advantage of in her designs. She began working independently as a tailor at the age of sixteen. As her reputation grew, she supported her family using a foot-pedal-operated Singer sewing machine in a small shop that could accommodate just a few customers at a time.

Kabuli women with high fashion tastes flocked to her because they said her hands were blessed. All she had to do was look at a design, and she’d be able to replicate it. And so women lined up to have western dresses, pantsuits with wide bell bottoms, a modest alternative to shorter dresses, and wedding dresses made by her.

My Jamila Khala always had her own space—a workshop filled with bolts of colorful fabric lining the walls, wooden boxes filled with the findings she needed to complete outfits, and a sewing machine. I first experienced her workshop when she visited Saudi Arabia during my childhood. My dad bought her a new electric sewing machine for the occasion. I can’t recall which bazaar we visited first, but we rushed to shop for fabrics almost as soon as she arrived.

She stayed in Riyadh for three months, sewing dresses for Saudi, Turkestani, and Afghan women, who often chose styles inspired by TV series or from French and American fashion magazines. As a child, this was the first time I had witnessed a woman who had her own dedicated space and a sacred time that was respected. During that period, I often interrupted others, even my dad in his dental office, which was always an open door for me.

My Jamila Khala’s space was forbidden to all until she opened it for someone to enter or for a lunch break. Then we’d sit cross-legged on the floor and drink hot cups of tea with samsa. Tiny triangle buns that fit my hands perfectly. It was a wondrous place with the sun pouring in and plants set about around the colors of fabrics. I don’t recall her ever using a dress form; years later, my friend Julie started studying fashion at FIT and used a dress form. There was a precision that involved a lot of math in her creation of beautiful outfits. And with her, as with my Jamila Khala, I tagged along to fabric stores, this time on Seventh Avenue in Manhattan.

My aunt created her designs using just a measuring tape, paper, countless pins, and her intuitive genius. From rolls of silk and taffeta—lots of taffeta—she crafted complicated, elegant evening dresses. Our home on the outskirts of Riyadh bustled with clients eager to have her create a dress for them after hearing about her arrival. I later learned that she was making couture dresses. The social scene was highly competitive, and women lined up for the opportunity to wear something designed by my aunt. She produced dresses in every color palette, all sparkling, puffy, and sometimes structured, but always regal.

She worked on these dresses alone. Amidst the glitzy styles of the 80s, she made a matching dress for both of us. It was a simple white dress adorned with tiny strawberries dotted all over. She used red piping to give the dress shape and to frame the strawberries on the cotton fabric. We took a photo by her sewing machine; I tilted my head toward her, holding some fabric in my hand while she focused on her work. In another photo she took with her to Kabul, we stood in the sunshine wearing our matching dresses. She looked beautiful in that picture—her long hair reaching down to her elbows. Unfortunately, none of these photos survived the many displacements that my family, my aunt, and her family faced.

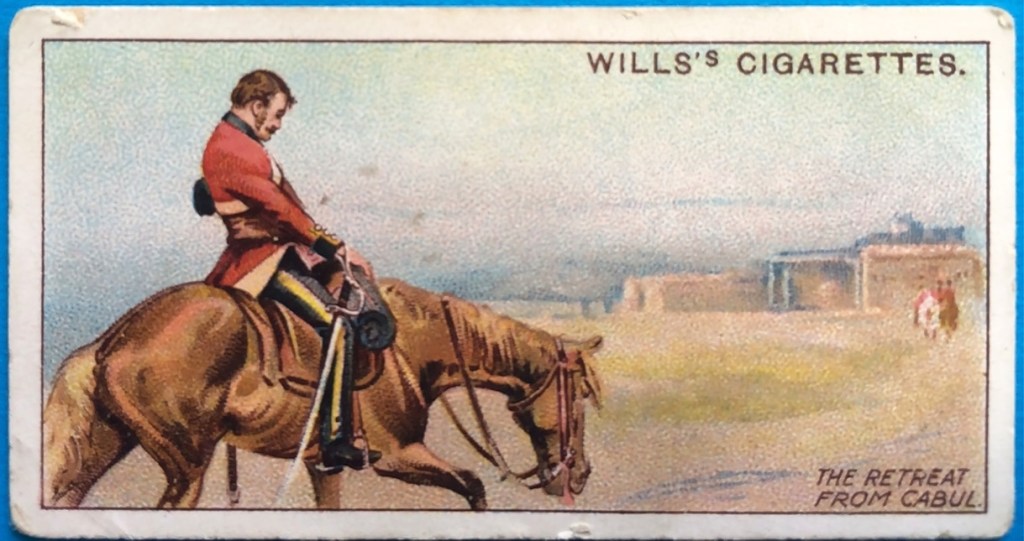

After her three-month visa expired, she returned to Kabul to gather the rest of her family, including her siblings and mother, who had not joined her on this trip. With her connections in Saudi Arabia, she managed to escape from the Communist regime, rescuing her family, friends, and even strangers—all thanks to the independence and resources provided by her sewing machine.

Writing is similar to sewing; it’s a quiet process that requires concentration and creativity, creating a sacred space that no one else can enter.

My beautiful aunts, Jamila Khala and Qamar Khala, my “Beautiful Moon Sisters,” in the 1980s in Kabul, Afghanistan.

Leave a comment